We Are Free Until We Reach the Fences:

- Nabuurs&VanDoorn

- Sep 25, 2025

- 4 min read

Nabuurs&VanDoorn’s Urgent Contact Zones

What is the task of art in this fractured world? In Penance and Rehabilitation, art does not console; it confronts. It does not signal with slogans, but moves through bodies, objects, and endurance. Seventeen videos, seventeen sculptures, a sound piece, a handmade map, and 100 scratched photographs stage encounters between history and the present, intimacy and collectivity, private and public. The work is a meditation on pain, memory, and resilience, a call to recognize that art matters precisely when the world threatens to disintegrate.

At the core lies the refrain: “We are free until we reach the fences.” The fence is both literal and symbolic: the limits of freedom, the boundaries of perception, and the barriers that separate empathy from action. In the videos, Nabuurs wields the camera as an instrument of authority, while Van Doorn enacts acts of penance, re-enacting historical methods of torture uncovered in archives. Real-time, single-shot sequences render the body fragile yet relentless. Endurance becomes a form of knowledge, luminous and untranslatable, arising through suffering.

The objects accompanying the videos, everyday items we inscribed with prayers to the Virgin of Fatima, materialize prophecy, history, and warning. Here, the sacred and the quotidian intersect. Their precision evokes the haunted terrain of horror, yet remains grounded in historical truth. The handmade map of Europe and the sound piece, recorded across seventeen sites in eight countries, situate experience in space and memory, tracing a network of scars, fences visible and invisible.

Now, in Berlin—a city of walls, divisions, and reinvention, the work resonates with renewed urgency. Penance and Rehabilitation functions as a contact zone in the Mary Louise Pratt sense: a space where disparate temporalities, histories, and bodies meet, clash, and converse. Power is asymmetrical: historical coercion, archives, and trauma confront the audience, who is implicated in witnessing, reflecting, and acting ethically. The work invites the audience into this space of encounter, where empathy, endurance, and reflection are activated and shared.

Looking back, the installation traces entanglements of history, memory, and intergenerational experience, revealing how personal endurance intersects with collective scars. Looking forward, it calls on us to inhabit these zones of reflection and action, to witness and reimagine freedom, and to transform public and private terrains with care, vigilance, and imaginative rigor. In this contact zone, spectators are not passive: they experience other lives, other histories, and other possibilities, and are invited to respond. Penance and Rehabilitation is therefore not only an archive of what was endured, it is a laboratory for empathy, reflection, and ethical engagement, a space where the precarious world we inherit can be felt, shared, and acted upon.

You can only scratch the surface text by Alicja Melzacka (2015)

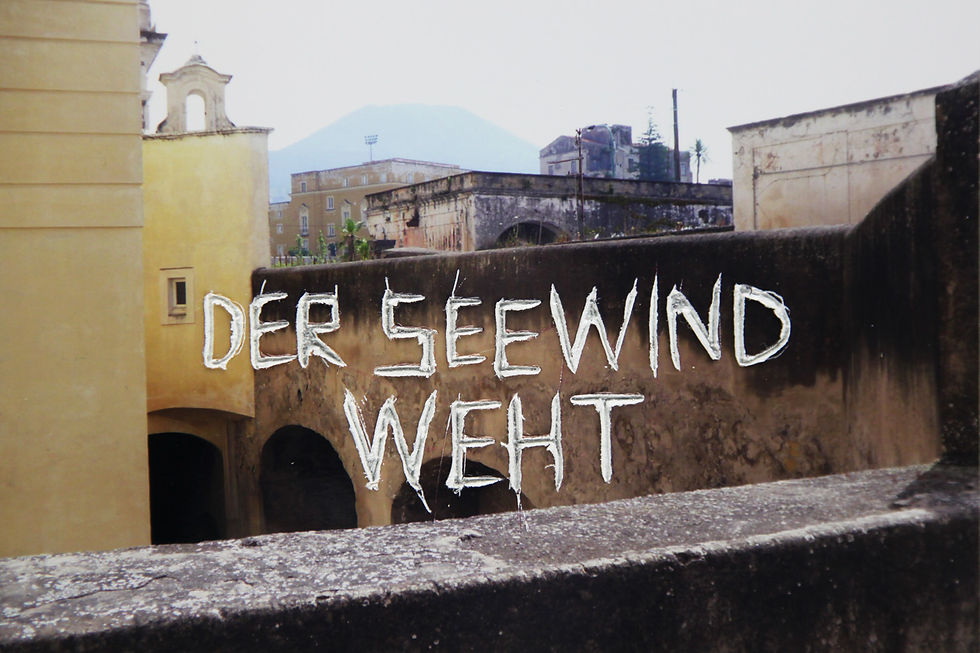

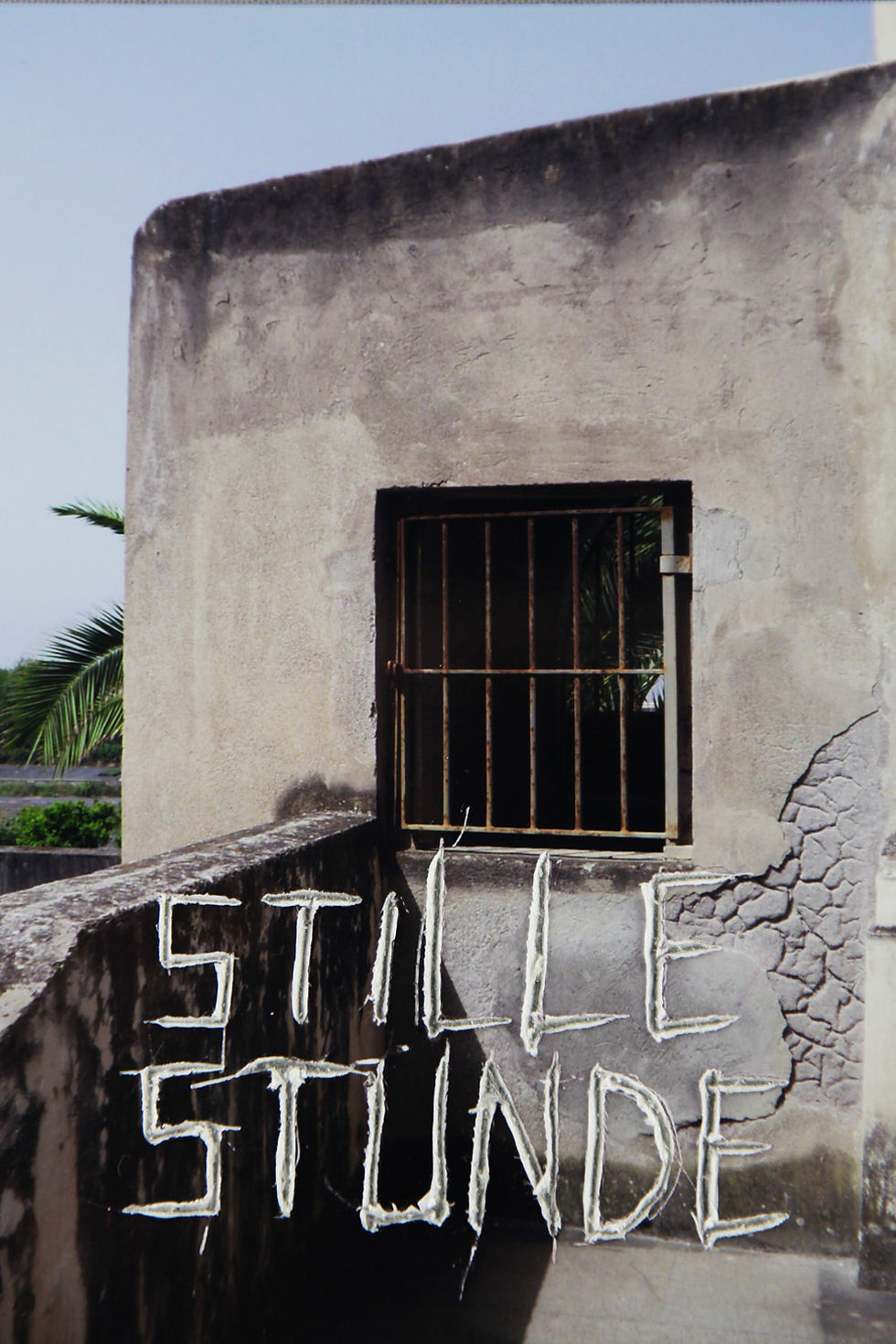

The series of scratched photographs x100 is closely related to another work by Van Doorn and Nabuurs – …but now it needs to be done… the video-series documenting public interventions performed by the artists in eight European countries, as a kind of a penance, or an exercise in submission. The same repentant dimension is manifested by the photographs; the locations depicted can be seen as lieux d’oubli, which have been deprived of their meaning either as a result of passive or active modes of forgetting. The role of photography, devised to document events of great importance or treasure precious moments, is here compromised as the images attempt to retrieve (or reconstruct) the unwanted memories, suppressed by the postwar strive for progress.

The particularity of this series results from the disruption laying at its basis – a common medium (photography) and a theme (landscape) is disrupted by an aggressive, almost sculptural gesture. Appropriated by Van Doorn and Nabuurs, scratching becomes a strong artistic gesture, shattering the usual illusion of space in photography. We are forced to abandon the three-dimensional seeing, as our attention is drawn to the cuts, forming the letters, syllables and words. Most inscriptions quote Wolfgang Borchert, a German writer associated with Trümmerliteratur. The roughness of the scratches corresponds figuratively to the way traumatic events become imprinted in the

collective memory. Wir sind die Generation ohne Bindung und ohne Tiefe said Borchert. However, there is something distinctive what bounds us nowadays – our inheritance, our post-memory. We live in the era in which constant restoration or reenactment of trauma has resulted in it becoming one of the constituents of the European identity.

Comments